It would be one thing if poetry were made of words alone,

but it is not–no more than words themselves are.

–Paolo Friere via James Scully (Linebreak 133)

…If essentialism means being able to name the rubrics within which we (women of color, African Americans, women, etc., etc.) may simultaneously be constrained, limited, subjugated by more powerful others and be nurtured, engaged, empowered by ourselves and our allies, then essentialism still has useful work to do in the struggle for social justice. I recognize the dangers it poses. I’ll stop identifying as an African American woman when most people in this society have stopped understanding me in terms of my proximity to those categories (and all the others that may be relevant to my subjectivity)–you first. Meanwhile, “networks of communities and…relationships” seems to be a productive model for describing my own activities in the world (of poetry). The focus on multiplicity potentially opens our eyes to connections that are predictable and unpredictable.

…This move turns on the significance to BAM “black aesthetics” of asserting a (“black”) “self” in the face of the oppressive and dismissive aesthetic standards that have been imposed upon the writing of African Americans since the era of Phillis Wheatley. An important point related to the foregoing is how critical it is for us to recognize that sexism is racism, at times, without losing the specificity of either category in our analyses.

…Whether one believes that poetry can affect or change what readers believe, can articulate ways of seeing the world that could circulate in and shape popular culture, can mobilize people for political action, etc., or not, poetry represents an economy of ideas (political, social, aesthetic, cultural) in which the currency is more valuable than it is often given credit for being.

“I have become a lot more aware over the past year or two

how often gender dynamics operate in really screwed-up ways

within a community I had complacently assumed was a lot more

progressive and enlightened than it sometimes reveals itself to be.

Just at the level, for example, of how much men outnumber women

on tables of contents, or how women’s comments are ignored in blog

conversations, or how men get threatened and aggressive when women

speak up about these things.”

–K. Silem Mohammad

…I’ll just add that the variety of forms that sexism takes is part of what gives it such reverberating impact: outright dismissals of women and women’s poetry; silence regarding the influence of women poets upon poetic traditions; lip service to the importance of poetry by women that doesn’t lead to structural change in the systems that construct and reflect what we value in poetry (the canon)–these are just a few of the forms in which sexism operates in the context of poetry. And, Tonya, of course, I deeply appreciate your extension of Spahr and Young’s observation about sexism to encompass racism and other structures of exclusion.

…If Audre Lorde is correct in saying that “poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought” (in her indispensable essay “Poetry Is Not a Luxury”), then it can be argued that envisioning and articulating what is desired but does not yet exist is one of the primary tasks–or, less prescriptively, primary opportunities–of the poet’s work.

…The very instance of thinking through the systemic reasons that result in or contribute to the inequitable representation of poets who are not white and/or not male will necessitate the consideration of factors that cannot be reduced to aesthetics, but have everything to do with aesthetics.

…I am arguing that avant-garde poetics need not be defined in opposition to either a discernable engagement with politics in the work or an interest in audience(s). Where did this avant-garde poetry/political poetry divide come from anyway? What motivated the surrealists? What motivated Dada? The high modernists? The Beats? The Language poets? Or should I be asking what distinguishes these politically motivated aesthetic movements from the New Negro Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement, the Nuyorican arts movement? And how does the most obvious answer to this last question relate to the notion of “a more radical feminism” and the intervention it could make in the world (of poetry)?

….I love Retallack’s concept of “pragmatically hybrid poetry communities” both because it seems grounded in immediate action and because it suggests the importance of seeking and forming alliances that don’t rely upon a mandated (false) unity around every possible issue of politics and aesthetics that might be raised.

…Can we accept and act on the idea that “transform[ing] the circumstances or conditions of others” may deeply involve transforming who we are and how we occupy the world (of poetry)?

–CONTINUED in “Dim Sum: Tonya Foster & Evie Shockley — Braiding: ConVERSations: To, Against, For”

~~

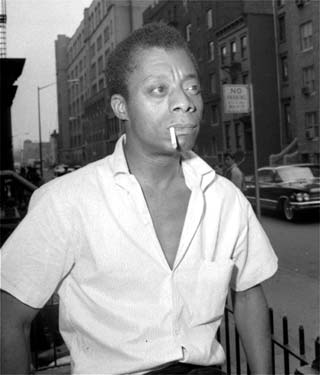

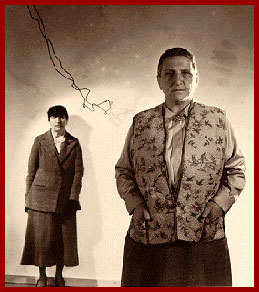

March 2nd, 2008 at 5:12 pm eEver notice how Evie takes the foreground of

pictures and the sound of readings? There is

a direct presence. No other.

March 2nd, 2008 at 7:43 pm eLooking over wrongs, I’ve noticed

over the years that oafishness and

subconscious deflection are often

the cause than intention and aggression.

Which is to say, maybe things are less

deliberate, more subtle, but paradoxically

harder to dig up. Just a thought from mulling

the comments I’ve seen by editors of both

genders for years. True Anthropology might

find more natural things than the old wounding

paradigms presupposed. If it could ever escape

the hothouse of likely well over 100,000 trawlers

trapped in an inland sea, and all the political

3rd rails, that is.

March 2nd, 2008 at 10:05 pm eOops…I am out of sync with the

aggressiveness thing that happened..

sorry bout the babbling.